Migration Postcard Project: #WeComeFromEverything

THE POETRY COALITION MIGRATION POSTCARD PROJECT: BECAUSE WE COME FROM EVERYTHING

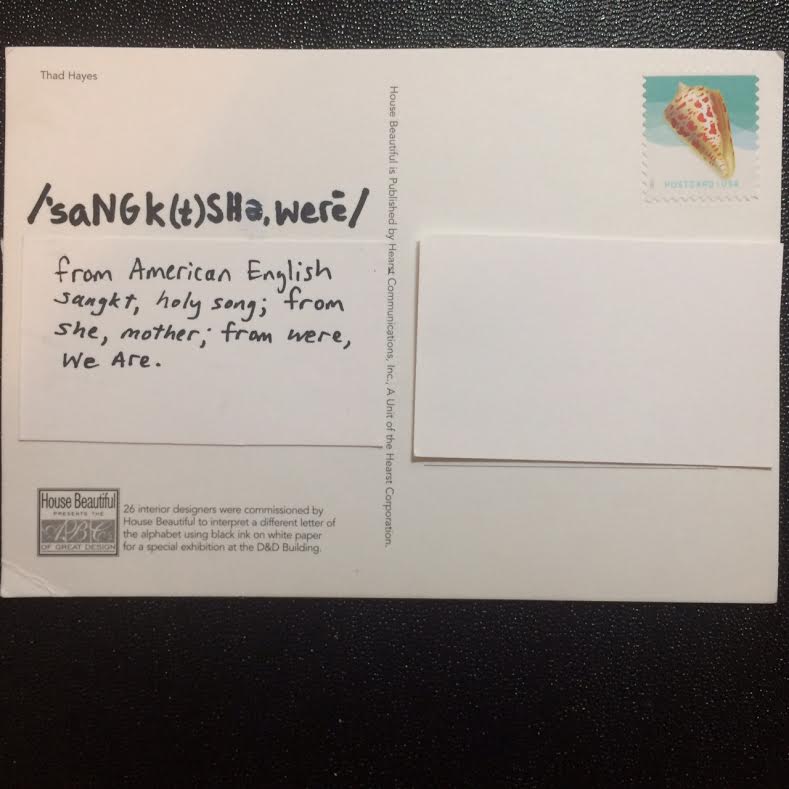

During the month of March, Kundiman fellows will participate in a Migration Postcard Poem Project called Because We Come From Everything: Poetry & Migration. Fellows will write and mail postcard poems highlighting the theme of migration.

Please join us by writing your own postcards and sending them out–– tweeting us @kundimanforever, using the hashtags #WeComeFromEverything and #PoetryCoalition. Email an image of your postcard to communications@kundiman.org–– we will be featuring select postcards on soical media, and on our tumblr.

Learn more about the Poetry Coalition

No somos nada y venimos de la nada pero esa nada lo es todo si la nutres de amor por eso venceremos

We are nothing and we come from nothing but that nothing is everything, if you feed it with love that is why we will triumph

We are everything hermana Because we come from everything

––Juan Felipe Herrera (from “Borderbus”)

Tiffanie Hoang

Pasadena resident Tiffanie Hoang on water and growing up in SoCal. She reads two [untitled] poems.

Tiffanie Hoang is a Vietnamese diasporic educator, poet, older sister, and daughter. She lives and works in Pasadena, CA. She misses the ocean, so she goes to the Korean spa.

Kenji C. Liu

Kenji Liu, a 2015 Kundi fellow, reads “How to be an Orange” and “Tree of Heaven.”

Kenji C. Liu (www.kenjiliu.com) is a 1.5-generation immigrant from New Jersey living in Southern

California. A Pushcart Prize nominee and first runner-up finalist for

the Poets & Writers 2013 California Writers Exchange Award, his

writing is in or forthcoming in The Los Angeles Review, The

Collagist, Barrow Street Journal, CURA: A Literary Magazine of Art and

Action, The Baltimore Review, RHINO Poetry, Best American Poetry's blog, and many others. His poetry chapbook You Left Without Your Shoes

was nominated for a 2009 California Book Award. A three-time VONA alum

and recipient of a Djerassi Resident Artist Program fellowship, his

full-length poetry book is currently searching for a home. He is a

poetry editor emeritus of Kartika Review.

Michelle Brittan

Long Beach resident Michelle Brittan reads “Poem for My Mother.”

Michelle Brittan has had poems published in Calyx, Crab Creek Review, The Grove Review, The Los Angeles Review, Nimrod, Pilgrimage, and Poet Lore, and in the anthology, Time You Let Me In: 25 Poets Under 25. In 2011, she earned an MFA in Creative Writing at California State

University, Fresno, where she won an Academy of American Poets Prize. Born in San Francisco, Michelle now lives in Long Beach and is a

doctoral fellow in University of Southern California’s PhD program in

Creative Writing & Literature.

Heather Nagami

Kundiman fellow, Heather Nagami, from Costa Mesa, CA and author of the poetry collection Hostile (Chax Press), reading her poems *Ritual* and *Ghost Algorithms*

Heather Nagami is a fourth generation Japanese American poet from Southern California. She is the author of the book of poetry Hostile (Chax

Press). Her poem

“Ghost Algorithms,” featured in this video, is being published by Four Chambers

Press in the chapbook Poetry and Prose

for the Phoenix Art Museum. She also

has poems forthcoming in A Literary Field

Guide of the Sonoran Desert and Zocalo

Magazine. Heather has taught at

Northeastern University, Pima Community College, and BASIS Oro Valley. http://www.spdbooks.org/Producte/0925904538/hostile.aspx

Brandon Som

Our first poet for the SoCal Asian American video oral history project: Brandon Som, an Echo Park resident and recipient of the 2015 Kate Tufts Discovery Award for his book The Tribute Horse.

Brandon Som is the author of the The Tribute Horse, selected by Kazim Ali for the 2012 Nightboat Poetry Prize, and Babel’s Moon, winner of the Tupelo Press Snowbound Prize. His poems have appeared in Barrow Street, Indiana Review, Black Warrior Review, Best New Poets 2007, McSweeney’s Poets Picking Poets, and elsewhere. He has received fellowships to the Virginia Center for the Creative

Arts and the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center. He holds degrees from Arizona State University and the

University of Pittsburgh and has recently earned his Ph.D. in the

Creative Writing and Literature program at the University of Southern

California.

Asian American Poets in Southern California, a video oral history project

Since moving from New York to Los Angeles three years ago, I’ve learned that while the Asian American poetry scene in NY is thriving,

Southern California is just as grand with talented Asian American poets

who offer perspectives rich with local landscape, culture, and history.

I’m happy to blog for the month of March and share with you a selection

of poets reading their poems for Kundiman Fireside. I hope you enjoy

this video oral history project of Asian American poets in Southern

California.

Love,

Lisa Lee

Kundi Fellow 2010

Interview with Heather Nagami

KUNDIMAN SOUTHWEST

An Interview with Heather Nagami

Briefly describe your journey to the Southwest and how this place has influenced your poetry.

Like many Japanese Americans, my great-grandparents came from Japan in the early 1900s and settled in California. I’m yonsei (fourth-generation), and I grew up in Southern California, where there were many others like me. I never wrote a poem about my race until I came to Tucson for graduate school when the abundance of cultural ignorance made it impossible to avoid. After completing the M.F.A. program and living in the San Francisco Bay area for a couple years, I moved to Raleigh and then Boston. I returned to Arizona because of my husband’s work, and I found myself compelled to write about race again.

Although I’ve met some wonderful people and have some amazing friends here in the Southwest, I’ve never been so often disappointed in people as I am here. In Arizona, you can be friends with someone for years and then feel stunned when she dresses up in yellowface for Halloween. In Arizona, you can think you know someone and then find yourself at dinner bewildered as he mocks Chinese accents. You can work at one of the top 10 charter schools in the country and still hear “That’s your English teacher? Does she speak English?” It’s the type of ignorance that’s neither hateful nor grave, yet I find it very hurtful. And in this way, Arizona reminds me that there still is work to be done. I have a unique voice, a voice that some don’t even realize or recognize exists, and I need to speak.

How has your Kundiman experience changed your life as a Southwesterner?

When I went to the Kundiman retreat in 2013, I felt like I was with family. Kundiman saved me then, and it saves me today. The fellows, the faculty, and the administrators all helped me remember who I am—someone who thinks poetry is possibly the most important thing in the world: it’s transformative, it’s political, it’s powerful and empowering. Kundiman reminded me that I’m not a freak: I’m just an Asian American poet. We see things that others don’t. We hear things that others don’t hear. And this is a gift.

After the retreat, I came back to the Tucson area and formed my own Asian American writing group. I also organized a Japanese cultural event, a mochitsuki, an entire festival centered around my favorite Japanese food: mochi. This is when I found out that in Arizona, you can celebrate your culture and a food that many have not heard of at all, and nearly 400 people of all ethnicities will come and celebrate with you.

What have you been working on lately? Do you want to share a poem?

When you look in a mirror, whom do you see? As a person who is very sensitive to how others see me, one image from the novel Jane Eyre has remained with me throughout the years: Jane is looking into a mirror in the red-room, and she sees both a fairy and an imp. I always took the image of the imp to mean that how she saw herself was partially derived from how her abusive aunt saw her.

Living in the Southwest, I find myself constantly at odds with how others see me, even when it seems positive. For example, I’ve met people here who think I’m really funny, like lough-out-loud-really-loudly funny. And while I’d like to think that’s true, I’ve realized a large part of their amusement comes from the fact that I’m not the stereotype they expect me to be—someone who is up-tight, boring, and without emotions; someone who doesn’t have a strong enough command of the English language to express sarcasm or irony; someone who is demure; someone who doesn’t say “like” and “you know” so many times.

C. Aurantium, the serial poem I’m currently working on, addresses these issues by, in a sense, ignoring them. In my daily life, I have accepted that I must explain myself to an audience who is comfortable seeing only a stereotype, but when I write poetry, I get to make the rules. I get to be the self, not the other, the center, not the marginalized. And when I look in a mirror, I see myself, my family, and my ancestors, including my poet ancestors.

The rule for this poem is that there is only one audience: poet and activist Mitsuye Yamada. It’s a tribute to her, a kind of thank you letter. It’s also an act of protest; I will only explain myself enough for Mrs. Yamada to understand, not anyone else. And while I say I’ve written these poems specifically for her, I would love for them to be read widely. There is something special to be learned in overhearing conversations, something unique that cannot be explained except by experiencing it yourself. Here is the title poem from the piece:

C. Aurantium

I wanted to call this poem “Kagami”

thinking mochi would enter

your mind, as it does mine.

Kagami mochi: mirror mochi

when I look

in the mirror

I see you

I wanted to call this poem “Daidai”

thinking family would enter

your mind, as it does mine.

Daidai: generation to generation

when you read

in these lines

my promise to you

But I didn’t like how dai sounds like die

nor how Kagami rhymes with Nagami.

I wanted to say thank you

but could barely find the words.

C. Aurantium: daidai

when we look

in the mirror

your legacy

Heather Nagami is the author of the book of poetry Hostile (Chax Press). Her poems have appeared in Spiral Orb, Shifter, Antennae, Rattle, and Xcp (Cross-Cultural Poetics). Heather received a B.A. in Literature/Creative Writing at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and an M.F.A. at University of Arizona. She has taught at Northeastern University, Pima Community College, and BASIS Oro Valley.

Interview with Jane Lin

KUNDIMAN SOUTHWEST

An Interview with Jane Lin

What has been the SW’s biggest challenge to you as an Asian American and a poet?

It’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, and as far as I know, there’s nothing special happening in Los Alamos except for the usual federal holiday closures. I’m not surprised. The US Census Bureau website reports only 2.5% of New Mexicans are “Black or African American alone” and in Los Alamos only 0.7% compared to 13.2% nationwide. When a black friend visited me in New Mexico for the first time, he said he would feel uncomfortable living here.

There’s a different kind of diversity here. New Mexico is known for its pueblos and Native American artists. With its Spanish colonial history, nearly half the population is Hispanic. Scientists come from all over the world to work at the two national labs in the state. Which is not to say that diversity means equality. But in my mind it helps when you’re not the only minority.

The deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner and the grand jury verdicts disturbed me greatly though they had little impact at the time on my remote mountain town. That disconnect challenges me. I could easily keep my head down and ignore the rest of the world, we are that isolated (there’s a reason why Oppenheimer picked Los Alamos for the Manhattan Project). So I make a conscious effort to be informed and stay connected. At the same time, it’s easy to feel helpless. Which is where poetry comes in. It’s a medium that allows us to respond to the myriad experiences of life including tragedy and injustice. When we share our poems, we participate in the conversation.

Months before Ferguson, police shot and killed James Boyd, a homeless man camping in the hills of Albuquerque. It was videotaped by police camera. People protested it as the latest in a series of fatal shootings. This month, Albuquerque made CNN when the DA filed murder charges against the two police officers involved. New Mexico is part of the national dialogue after all.

It surprised me when people said they couldn’t understand the response to Ferguson. How often are we frustrated when the systems meant to help us fail us instead?

After the Verdict

Because my mother preferred to help than be helped,

she kept her cancer secret.

Which is to say I tell myself today, do not despair

though our country remains unchanged after each shooting.

We all have our ways of coping.

My fumbling, stumbling out of silence.

Which is to say, dear reader, I don’t want to go it alone.

My mother had a strong sense of right and wrong.

Which is to say there is nothing right about children shot dead.

The circumstances of her death, their deaths,

fill me with anger and grief.

Black lives matter. As in equally, yours and mine.

How has your Kundiman experience changed your life as a Southwesterner?

I was lucky to meet Arthur Sze not long after moving here in 1998. Previously I lived in New York and California. Perhaps because of his long established presence in the area and many years of teaching at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), I never felt unusual as an Asian American poet in New Mexico. He was in fact the first poet laureate of Santa Fe. I have always felt respected and treated for who I am as an individual by other people here. Though I have to admit that an Asian American artist in Sante Fe told me someone mistook her for me!

What Kundiman gave me last summer was a door to a larger community which made me feel less isolated. This very blog allows me to participate still. The diversity of the fellows, faculty and staff and their art expanded my vision of not only poetry but of life. And most of all, I have found connection with my fellow Kundiman Southwesterners Heather Nagami and Sharon Suzuki-Martinez even though they are 500 miles away and I’ve never met them in person! Maybe that’s the magic of poetry and of Kundiman - we can celebrate both difference and commonality.

What is the poetry scene like where you live? Where’s the best place to go for a poetry reading?

Los Alamos has a great public library which hosts Quotes: The Authors Speak Series highlighting New Mexican writers. Unquarked, a new wine tasting room, plans to hold monthly poetry readings.

Down the hill, Santa Fe is home to the Lannan Foundation which hosts an inspiring array of writers and cultural thinkers in its Readings and Conversations series at the Lensic Performing Arts Center, a beautiful restored theater down the street from the 400-year-old Santa Fe Plaza. A few blocks away is a terrific bookstore called Collected Works which hosts the Muse Times Two series curated by Dana Levin and Carol Moldaw. This series pairs a regional poet with a nationally known poet.

There is always something going on in Santa Fe, not to mention Taos and Albuquerque. Other SF venues include IAIA, Santa Fe University of Art and Design, Teatro Paraguas, and op.cit. Teatro Paraguas specializes in bilingual theater, and it is a real treat when they produce performances of Spanish-language poets. Also, IAIA has a low-residency MFA program, and you do not need to be Native American to apply!

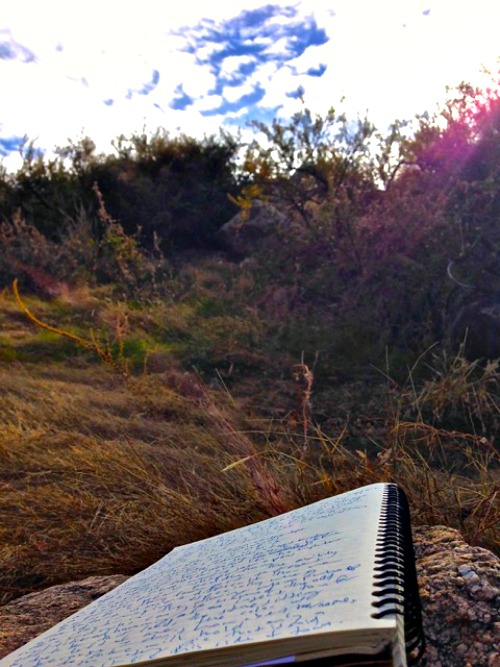

Talk about the most inspiring place in or near your home. Send a picture.

Los Alamos sits at the tail end of the Rockies. I can walk a few blocks from my house and be in a canyon or on a mountain trail, but my favorite is Deer Trap Mesa. I drive 10 minutes past houses, park at a dead end. The asphalt crumbles past a guard rail. Dirt gives way to tuff, volcanic ash become rock. Quickly the land narrows, drops off into canyons on either side. Scrambling down to the right would reveal small shallow caves with sooted ceilings. I pick my way forward along a fragile path – grooves first shaped by the footsteps of Ancestral Pueblo people 500 to 800 years ago. Down there is a rectangular hole – an ancient deer trap. Up again the finger mesa continues, widening with scrub, grasses, low-lying cacti. This is high desert. The path winds among junipers and pines hiding the view until I come out at the tip. Suddenly I can see for miles—valley, mesas, Taos, Santa Fe, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the tremendous sky.

Interview with Sharon Suzuki-Martinez

KUNDIMAN SOUTHWEST

An Interview with Sharon Suzuki-Martinez

(photo credit: David Martinez)

Poets of color face a unique type of adversity in the Southwest. Can you describe what you have encountered? How has it hurt or helped your poetry?

Scholars have written about America’s anti-intellectual tendencies throughout history. Nevertheless, I am puzzled to live in a place where if people go to college: they tend to matriculate as conservatives, and then graduate as conservatives. One of my former co-workers, a redheaded ASU graduate, told me she “hated” to see people of color on TV, and made fun of my slight Hawaii accent. Research shows that the core conservative values are “resistance to change and support for inequality.” This culture of anti-learning and pro-stereotyping explains how people can assume I’m foreign (and insist Hawaii is a foreign country), believe Chicanos are drug-smuggling aliens, African Americans are born killers, and Native Americans are/should be extinct. Many Arizonans don’t even TRY to get to know individuals from other ethnic groups, or can’t see that stereotypes are proven wrong in chance encounters every single day.

Some people glance at my Pima husband, and my waist-length hair and assume I’m some sort of American Indian too. I’ve been mistaken for the Navajo Poet Laureate, Luci Tapahonso—not a bad thing! I prefer looking ethnically ambiguous even if it makes retail workers and the police more suspicious of me. Let me explain.

I’m still haunted by an incident in the early 90’s when I was a doctoral student at the University of Arizona in Tucson. I was at a conference geared for high school teachers and had just presented on teaching Maxine Hong Kingston’s Woman Warrior. I was the only Asian American in the room of White, Black, and Chicano women. Somehow, the group discussion exploded into the teachers angrily blaming Asian women for making things bad for all other women. As if their husbands were dicks because of me. They took the submissive, geisha stereotype as self-evident truth so they didn’t see themselves racists. They scared the f***ing hell out of me—flashback to nearly getting beaten up in the girls’ locker room in 7th grade. I don’t feel safe alone among strangers while being openly Asian in Arizona.

I am not sure how this racial climate has affected my poetry, but I constantly wrestle with cynicism (the enemy of creativity) and am mostly unknown as a Phoenix or Asian American poet. The great thing is I’ve never been pressured to limit my writing to Arizona or my ethnicity; I am free to go wherever I please in my poetry.

What is the poetry scene like where you live? Where’s the best place to go for a poetry reading?

When my husband and I first moved from Minneapolis to Tempe in 2007, ASU poet Laura Tohe told me via email that the Phoenix metro area didn’t have a poetry community. That was confirmed when a local poets’ group with a website inviting new members ignored my attempts to communicate them. I was shocked by how different the literary scene was from Twin Cities.

Part of the impetus for creating The Poet’s Playlist was to create a poetry community not tied to a particular location. There are poets from all over the US and Canada talking about their poetry and sharing their favorite music on my website. That project has been as gratifying to me as belonging to Kundiman, which is also dedicated to connecting across miles through poetry (and fiction starting this year).

That was a roundabout way to answer the question. Although I’m still an outsider, a lot has changed since 2007 and now the Phoenix poetry scene is on fire with more poets, literary journals, workshops, and many reading series. My favorite poetry series is the Tempe Poetry in April, but its future is up in the air. Other than that, there is ASU’s Virginia Piper Center’s Distinguished Visiting Writers Series, the Phoenix Poetry Series, Caffeine Corridor Poetry Series, Lawn Gnome Publishing Poetry Slam, Matador Open Mic Poetry, Balboa Poet House, Changing Hands Bookstore’s First Fridays open mic, and many more small open mics across the Phoenix valley.

How has social media affected your work?

It’s a strange time to be a writer. I might be wrong, but authors cannot afford not to have social media presence—no matter how seemingly counterproductive it is to their writing. But that makes Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Wordpress, etc. sound like nothing more than a necessary evil. I think connecting with your audience, or potential audience is always a good thing. Social media helps us remember the people we are writing for. Twitter, in particular, helps hone my ability to write succinctly and practice one-liners. The danger lies in missed opportunities, in not developing poetic tweets into poems.

Would you like to share a poem you’ve written while living in the Southwest?

Here is something partly inspired by a drive through Phoenix, during the height of the Ferguson protests. Thank you, Kundiman SW (Heather Nagami and Jane Lin) for your feedback and camaraderie!

Guns Save Lives

Says the sign at the bus stop, but

to follow the logic of, “Guns Don’t Kill

People, People Kill People,”

means guns don’t actually save People either.

(Unless Jesus is a pistol)

Guns can’t kill or save lives

because they are inanimate objects,

like pillows.

Pillows are innocent,

but also used by People to kill other People:

vicious sleeping or vegetating People.

(Flashback to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest)

Perhaps we should content ourselves

with pillows instead of guns.

Let’s stockpile pillows

like we are hoarding puppies.

The fluffier

the better.

Sharon Suzuki-Martinez is a sansei Okinawan-Japanese American originally from Kaneohe, Hawaii who now lives in Tempe, Arizona. She is the author of The Way of All Flux (New Rivers Press, 2012), winner of the New Rivers Press MVP Poetry Prize. She created/curates The Poet’s Playlist. She has been a Kundimana since 2008.

Tweeting at @SuzukiMartinez

Lessons from BROWN BEAR, BROWN BEAR: II

This week’s posts are an attempt to understand the influence of parenthood on poetic practice. How do these (sometimes conflicting, it feels!) vocations inform one another? How can the reading habits of the very young help us become better writers? Better readers? And what can poetry teach us about parenting?

Recently, my daughter has begun spotting “Dog” everywhere. In books, during walks, embroidered on decorative pillowcases at Anthropologie (no, that’s a fox, darling…). She points, mouth puckered into a little “o” of discovery, grunts “ohh— ohh—.” We think this means “Woof, woof,” which makes sense, since now that I’m a parent, I’m weirdly incapable of pointing out any fish, fowl, or land animal without also asking, “What does the _____________ say?”

When “reading,” she searches out pictures of dogs and will flip pages furiously until she finds one. “Ohh, ohh.” Are we so different, as poets? We’re drawn to recognizable forms, images that haunt. The hand pressed against the windowpane. The stained coffee mug in the sink. These motifs emerge, ghostlike, everywhere in our poems. I recently taped the pages of a manuscript I’ve been revising up on a wall, only to see the word “face” appear over and over again. An unnerving experience, considering that it was never my intention to write a project about the human face. Yet, there it is. Face, face.

What haunts us, draws us back? Dog. Dog. Soon we’re searching for it everywhere, spotting it in places that bear only the remotest likeness. Teddy? Panda? Close enough. This is the poet-mind that latches on to a form and, once recognizing it, fixates and will not let go. Whether we’re aware of it or not, we’re often claimed by some cadence or unusual image, which holds on until it’s through.

It’s possible that we’re not that far removed from our infant selves: pointing, naming. Ohh! Ohh! Our poems are sparks of recognition, moments of familiarity in the midst of life’s bewildering muddle. Or, they’re attempts to render the unfamiliar in terms we can understand, to build a linguistic apparatus by which we can make (sometimes mistaken) sense of the world. That creature there—black and white patches on its face, a striped tail— Dog? No, darling, that’s a raccoon… But what matters most is the mind at work, the act of perception. The art’s in the articulation.

Mia Ayumi Malhotra is a 2012 Kundiman Fellow and the mother of a ten-month-old. She teaches and lives in the Bay Area. Visit her website at miamalhotra.com.

Lessons from BROWN BEAR, BROWN BEAR: I

This week’s posts are an attempt to understand the influence of parenthood on poetic practice. How do these (sometimes conflicting, it feels!) vocations inform one another? How can the reading practices of the very young teach us to become better writers? Better readers?

As a new mom, I’m delirious from months of midnight feedings and subsequent weeks of sleep training. Some days, my mind and body feel utterly depleted. Yet, I’m convinced that being a parent doesn’t negate my being a poet. In fact, I suspect that it could deepen my practice, if only I had the time and energy to figure out how. Here are some of my recent thoughts on how mothering informs my understanding of poetic practice.

As a reader, my daughter isn’t particularly discriminating. Anything will do: Crate & Barrel catalogues, The New Yorker, flyers from our local dentist. At this age, she likes books for their material quality. The way they fall open in her hands. The fact that, with each new spread, a different panorama of image and text lies revealed before her. She likes to handle the pages, to flip and crumple them. Some of her recent favorites are Melissa & Doug’s Farm Tails, The New Yorker (to chew, admittedly), and, of course, Bill Martin Jr. and Eric Carle’s classic Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?

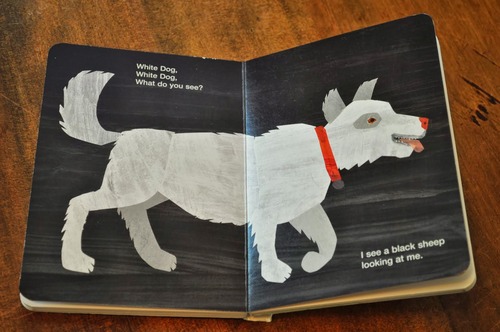

Here is what reading looks like. She examines the first few pages of Brown Bear, Brown Bear, flipping them back and forth. The narrative, a fairly straightforward, linear sequence of sightings and questions, is disrupted. Unusual pairings emerge. Green frog! Purple cat! Green frog! Purple cat! Perception morphs; a brown bear becomes a yellow—a blue—a green—!! At times, all this arbitrary page-turning generates suspenseful litanies of text marked with an intensity of rhythm not present in the book’s standard reading. I see a blue horse! A green frog! A white dog! A purple—! Expectation builds, and then it all comes tumbling down. Yes, that’s right, we’re back to page one. Back to Brown Bear.

The flipping back and forth, the circularities and jump-cuts—all this can feel very random, but the reality is that, as poets, we’re always in the same book, bound by a consistent set of syntactical structures. Driven by contradictory impulses, we’re moved by a parent, guiding principle, which leads us through the narrative, nudging us toward the “close,” but then, there’s the other part as well, that which forestalls the ending. Resists the flow. This second impulse is the one that, once we’ve reached the climax, pulls back precisely at the moment of resolution and lands back on the same old “Brown Bear, Brown Bear” of the opening page. Both forces are vital in our writing. The energy generated by their contradictory impulses (the parent reading forward, the child flipping backward) can become a powerful dynamic in our poetry. At the Kundiman retreat several years ago, visual artist and poet Truong Tran advised us to allow readers to wander through our poems, to conceptualize our writing as labyrinths. Leave a few doors open. Don’t foreclose meaning. Give permission for Brown Bear, Brown Bear to be read in nonstandard ways.

To be perfectly honest, I think my daughter mostly likes the experience of being read to. Sure, she’s drawn to the images, and many of Eric Carle’s collages are beautifully textured, but really, I think she just enjoys listening to my voice. As readers (and writers) of poetry, we understand. It’s that sense of being spoken to—sung to, even—that keeps us coming back. Poetry’s magic lies in its ability to fashion within us the feeling that we’re being spoken to by someone who cares that we’re there, listening. It’s why we read: to hear another’s voice as it animates language in a way that delights and instructs. At the end of the day, what we’re after is an encounter with a voice that engages, reveals, and above all, draws us into a circle of intimacy and embrace.

Mia Ayumi Malhotra is a 2012 Kundiman Fellow and the mother of a ten-month-old. She teaches and lives in the Bay Area. Visit her website at miamalhotra.com.

UMBRELLA/SHIELD POETICS (part iii)

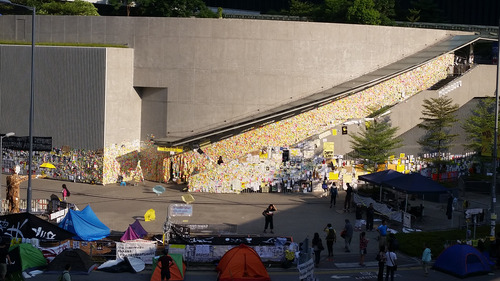

This second week of the Kundiman NorCal Regional Group’s Fireside brings a special interest from Hong Kong and the ongoing Umbrella Movement protests. Kundiman fellow Henry W. Leung writes:

*

On the English shelf of a styrofoam library at one protest site, naturally, there stands Kiran Desai’s Inheritance of Loss:

The simplicity of what she’d been taught wouldn’t hold. Never again could she think there was but one narrative and that this narrative belonged only to herself, that she might create her own tiny happiness and live safely within it.

More narratives are visible in Hong Kong now than just the ones officially told or sold. Signs and posters hang from walls and clotheslines, are pasted directly over billboards and commercials. The language of protest takes on an attitude of graffiti, in the sense of Banksy, in the sense of Wall and Piece:

Any advert in public space that gives you no choice whether you see it or not is yours. It’s yours to take, re-arrange and re-use. […] They have re-arranged the world to put themselves in front of you. They never asked for your permission, don’t even start asking for theirs.

But there is no vandalism. There is no hidden war here. And, anyway, these quotes are from a different subjectivity, someone else’s cobwebs on the windowpane.

* *

Fleurs des Lettres (字花), a literary magazine in Chinese, has printed poems and essays, organized a library, screened The Strawberry Statement (1970), and mobilized readings and talks by writers at the Mobile Democracy Classrooms. The schedule for such talks (and their variations, e.g. the Umbrella Square Tutorial) appears daily on handwritten signs at the three main protest sites. I’ve been to lectures and discussions on Xi Xi and Lu Xun, minority rights, feminism, and the biochemistry behind ebola outbreaks. All this grew out of the first week of student strikes in Tamar Park—before arrests, before occupation sites, before tear gas, before clashes. The schedule from that week’s outdoor classrooms is here with English, and here are videos and full transcripts (mostly in Chinese).

from Law Wing San’s talk on Vaclav Havel and Post-Totalitarianism:

A person lives in one of two existences: ‘living in truth,’ or ‘living in lies.’ These are fundamental states—but perhaps, comparing the two, might there not be more? We’ll see how authority doesn’t just concern what is given to us, but even more in what passes through our hearts, what passes through our ways of seeing and choosing our existences.

from Kacey Wong’s talk on using art to change the world:

Sometimes I see the news—yesterday another person arrested, another page torn away—and just like that I’ll call a friend to say: “Ai Wei Wei’s been arrested, should we do something?” And my friend will just as easily reply: “Of course! We should do something!” […] But if everyone thinks this way yet doesn’t act, the result is that nothing changes. It only abets the negative. Thus this golden line from Goethe: “Knowing is not enough, we must apply.”

* *

In the second week—after the outbreak of thug violence—a poem by Tammy Ho Lai-ming appears online: “How the Narratives of Hong Kong are Written With China in Sight.” It’s a series of adapted first lines. This one offers a key to the form, its friction and irony:

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the democracy fighters in Hong Kong must be genomically modified by the West.

The poem begins from Melville and ends from Beckett; begins in the imperative/declarative and ends in questioning, in a rupture of sense.

In the first week—after the pepper spray and tear gas—a poem by Nicholas Wong appears online: “Before enduring it we will not endure it.” It’s a series of fragments without stops. “I was searching for the capacity for the third,” he writes. Borrowed text slips in from other voices, other poets, like this first clause italicized, from Olena Kalytiak Davis:

Of all the forms of being—I like a vote, an animal. And you, captive, erosive, crevassed

The polyphony is another kind of rupture: a shared voice, a grievous sharing.

In the beginning—after students are arrested for climbing into Civic Square and sitting—an essay by fiction writer Dorothy Tse appears online: 〈縮骨遮的想像力〉 She writes:

What was the crime of those hundred and more who trespassed over the boundary? Deep gratitude goes to them, who sacrificed themselves, who braved real dangers, who showed us the trespasses of our own boundaries. They awakened our imagination, its possibilities.

* *

Every day here will be a book on a shelf somewhere. But who will anthologize the words? Who will archive all that is beautiful and temporary? Who will record not just faces but, at long poetic last, voices? When the smog returns and commercial calm rolls back, who will count and account for all the votes pasted into wind?

I’m drafting this note while seated on a recently built bench labeled 只共自修 (shared self-study only) at a recently built table, in the study area on the highway in the middle of Umbrella Square. Wifi has been set up here, along with LED lamps, recharge stations, and a help desk. People keep coming by to offer me homemade bread and rice boxes, while across the way police officers at a government cafeteria sit by the window chatting and watching us over milk tea. The sun sets in a gap between the Lippo towers. People have been hammering and sawing behind me for hours, building more desks. All things here are sturdy. All things here are disposable.

It’s not enough to know; these words will not do. I’m trying to give a glimpse of something to you, something like the miracle of a heron walking on water in Victoria Harbor even while policemen run along the highway with riot shields. I’d like to give you poems in English dating from the White Paper to today. I’d like to give you satire news cartoons (with subtitles), music and a playlist of more music, collections of visual art and more visual art, a clay workshop reenacting major clashes, and an ongoing archive of the Lennon Wall where thousands of post-its answer: “Why Are We Here?”

I’m giving you a love that expires and tarnishes, but only in the way libraries do. I’m asking: what will be enough? I’m stepping aside so you can see, but you have to see, because you have to see.

* *

from Chang Nam Fung’s talk on his half-mainlander perspective:

Now, I don’t know why becoming old means becoming conservative, while the young have fervor—isn’t that strange? I hope no one sitting here grows old. If this were so, even the multitudes would never grow old.

* *

(All photos, except the first, are courtesy of Vivian Yan. All translations, errors, and haste are my own.)

* * *

UMBRELLA/SHIELD POETICS (part ii)

This second week of the Kundiman NorCal Regional Group’s Fireside brings a special interest from Hong Kong and the ongoing Umbrella Movement protests. Kundiman fellow Jennifer S. Cheng writes:

*

…and in the pale light of the shadow we put together a house.

—Junichiro Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows

*

To understand the protests in Hong Kong, you have to understand its history. Before it was a “Special Administrative Region” of the People’s Republic of China, it was a British Crown colony, a treatied concession, a land leased. For 156 years, the people of Hong Kong lived under “foreign rule,” though at some point foreign becomes a slippery notion, a term submerged in water. You can talk about the cultural influence and formation during this century, you can talk about hybridity, you can talk about its greater freedoms in comparison to the mainland, but at least equally relevant is that, in some ways, Hong Kong was never entitled to its own identity, never permitted its own voice. (And doesn’t liminality have to do with a longing for a voice?)

.

From Ackbar Abbas, Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance:

“Postcoloniality…means finding ways of operating under a set of difficult conditions that threatens to appropriate us as subjects…for example, thinking about emigration in a certain way, emigration not in the diasporic sense of finding another space…with all the pathos of departure, but in the sense of remaking a given space that for whatever reason one cannot leave, of dis-locating.”

.

It is a city that protests: July 1, June 4, Occupy Central, hundreds of thousands, hours of marching, candlelight vigils, a crowd of bodies singing in unison. It began perhaps with 1989, one-sixth of Hong Kong’s population emerging in support of the students across the waters; in the years after the 1997 Handover, pro-democracy protests swelled. This history of public demonstration is yet another mark of disjuncture from “Chineseness” in a city already anxious about identity. When you are one in thousands, a body among bodies, sitting and lighting flames one by one, neighbor to neighbor, you cannot but ask, Why are all these bodies here? What heat do they feel inside? When you are one in a night on the street, sleeping side by side. Perhaps one articulation is that the city protests because that is a freedom afforded to it: an avenue for voicing itself: Hong Kong protests because it can.

.

“[Hyphenation] points precisely to the city’s attempts to go beyond such historical determinations by developing a tendency toward timelessness…and placelessness…a tendency to live its own version of the ‘floating world’…not as a neither-nor space that is nowhere; not even as a mixed or in-between space, if by that we understand that the various elements that make it up are separable. Above all, hyphenation refers not to the conjunctures of ‘East’ and ‘West,’ but to the disjunctures of colonialism and globalism…a very specific set of historical circumstances that has produced a historically anomalous space that I have called a space of disappearance” (Abbas).

.

To conduct research into Hong Kong history, linguistics, culture is to learn the terms hybrid, liminal, floating. If we were to say hybridity as identity, liminality as identity, it is because the history of belonging is one that eludes. We do not know exactly how to define the boundaries, how to draw a concrete outline. We do not know what the blueprints look like, where they are stored. Nineteen nights now, in the streets: timelessness as time, placelessness as place.

.

From Rey Chow, Between Colonizers: Hong Kong’s Postcolonial Self-Writing in the 1990s:

“Hong Kong’s postcoloniality is marked by a double impossibility—it will be as impossible to submit to Chinese nationalist/nativist repossession as it has been impossible to submit to British colonialism.”

“What would it mean for Hong Kong to write itself in its own language?”

.

(Or: What is the poetics of longing?)

**

Note: The 1993 Canto-pop song 海阔天空 (“Boundless Sea and Sky”) by Beyond has become an anthem for the Hong Kong protests for its heartening lyrics and its local, nostalgic significance. The chorus can be translated as: Forgive me this life of uninhibited love and indulgence of freedom / Although I’m still afraid that one day I might fall / Abandon your hopes and ideals, anyone also can do / I’m not afraid if someday there’s only you and me. The singer, 黃家駒 Wong Ka-Kui, died the same year the song was released, so in some ways it is also a memorial. Another song that has been adopted is rather a song that has been adapted: “Do You Hear the People Sing?” from Les Miserables. The Hong Kong version in Cantonese goes beyond translation and rewrites the lyrics: Who wants to succumb to misfortune and keep their mouth shut? / May I ask who can’t wake up? / Listen to the humming of freedom / Arouse the conscience which shall not be betrayed again.

**

**

First photo by Vivian Yan.

Second photo by Henry W. Leung.

***

UMBRELLA/SHIELD POETICS (part i)

This second week of the Kundiman NorCal Regional Group’s Fireside brings a special interest from Hong Kong and the ongoing Umbrella Movement protests. Kundiman fellow Henry W. Leung writes:

*

Begin with the pretext of song.

All songs are love songs.

Make the text unrequited.

Kung hindi man, isn’t it?

“If you will not,” or: “If not for…”

Then make the text your name—

Kundiman—only—

Consider the colonial history—

Consider the example of the blues: a rhythm of a spiritual developed from the labors of long slavery where the notes for the loss of the beloved, sliding between the minor third and flatted third, that mythic blue space non-existent on a western scale, at once affliction and libation, which isn’t really about the loss of the beloved after all but the loss of a motherland—

What is more unrequited than home—

*

I’m writing this as a reminder that one of the cornerstones of our community is the shared sense of unbelonging. A kind of homelessness. I’m writing this barefoot on a bedsheet on a highway in Hong Kong, at rock-throwing distance from the government offices and the PLA garrison. This [Oct 12] is night fifteen of the Umbrella Movement. The shifts—to hold the line—change as many times daily as do the news and atmosphere of civil disobedience. I’m writing to report that it is neither romantic nor cool nor comfortable to camp on black asphalt under street lighting in the wind. It is not a story to commodify. Hundreds have been here each night, holding space for thousands to gather in the day and continue protesting for genuine universal suffrage. In various iterations, signs and posters declare: “Hong Kong is my home.” This is being demonstrated on the streets as a kind of homelessness.

I’m writing this as a reminder of why you should care. You skeptics at a distance who, like me, stutter over mixed feelings and broken lines, you poets and artists and caretakers of a vast diaspora, who are never native enough in America or the other motherlands that claim you: don’t you hear the holler of a village oceanic, on these looming high roads of stone, this “borrowed place of a borrowed time,” caught between empires, calling finally for the eloquence of a home of its own?

I’m not writing to you about democracy, or justice, or morality, or solidarity, or nationalism, or revolution. I’m writing to you about the first night of every Kundiman retreat when we open the circle and look into faces matured in wounds of longing, and listen. I’m writing about what it means to be a liminal human being hungry to be understood on your own terms.

First, there wasn’t enough news. Now, there’s too much news. There’s not enough listening. Whether you say the protests are just, or irresponsible, at least say they’re important. All the clash and clamor here are the messy articulation of a voice coming into being. And—forgive me this leap—I can’t help hearing in the voice a personal challenge, the reminder of another: here is Audre Lorde, speaking in 1977:

“What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence? Perhaps for some of you here today, I am the face of one of your fears. Because I am woman, because I am Black, because I am lesbian, because I am myself – a Black woman warrior poet doing my work – come to ask you, are you doing yours?”

I’m here, an Asian American poet outsider, doing my work. This and the following posts are a collage of words in an effort toward that work, toward understanding. Translations of poems and essays from the movement will be coming soon in APIA and social-action literary journals. The Kundiman NorCal Regional Group is putting together a related literary event in the coming weeks. Please sit with us and listen.

**

(Photos courtesy of Vivian Yan, who blogs here.)

*

Note: The umbrella came to be the symbol for the movement when protesters shielded themselves from police pepper spray on Sep 28 by turning their umbrellas inside-out. International media dubbed the movement the Umbrella Revolution, though the leadership here insists on Movement (運動) to avoid associations with recent “color revolutions” and violent uprisings. In formal written Chinese, the word for umbrella is 雨傘 (yusan), but is seldom used in Cantonese because 傘 is homophonic with 散, which means “to disperse.” So the common term for “umbrella” in Cantonese is 遮 (zhe) which also means “shield” or “shelter.”

*

www.scmp.com/topics/occupy-central

http://hongwrong.com/occupy-central-live/

@OCLPHK

@HKFS1958

@hkstream

@TranslateHK

@varsitycuhk

@HKStudentStrike

@Scholarismhk

***

Cristiana Baik

by Cristiana Baik; photographs by Crystal Baik

Space has temporal meaning in the reflections of a poet, in the drama of migration.

*

It’s dusk, a surprisingly dry summer night in Pyongyang.

I’m standing on a paved road that quietly unfurls for 110 miles. The horizon’s salmon glow is quickly darkening into blue and a pace of shadows — quick movements, whispers and echoes. The “Arch of Reunification” — a statue of two women who together raise a sphere with a map of a reunified Korea — towers over me. I ask one of my peers from the NY-based delegation how far the capital is from Seoul. She says softly, as if not wanting to disturb this last glow of summer day: Only two hours. 120 miles.

*

The feel of a place is registered in one’s muscles and bones.

*

"Parsing the archive means listening for images and sounds in the eye of memory. It calls for hearing a nonspectral acoustic register, the sounds of people scattering in flight, speaking in hushed voices, testifying bravely, remembering through stories marked by song, nicknames, poisoned images, and weeping."

*

A friend recently shared her latest film project, entitled Reiterations of Dissent.In the first portion of the film, which explores the perceptible traces of the “4.3” incident — a 1948, U.S.-sanctioned massacre that resulted in the deaths of an estimated 30,000 Jeju residents — a succession of landscape images of Jeju-do, an island known for its verdant and lush foliage, fills the computer screen. A wild flock of crows descend and gather about the floor of a forest, a haunted place where residents were shot and murdered.

The narrator says he barely remembers the incident (he was only seven when the island exploded in violence). “4.3 has remained only a whispering sound,” he says.

What does a constant cry of crows circling a sky, frenzied to search for what cannot be discovered, tell us? Are horrible and unspeakable events passed on, generation to generation, always in whispers, never in screams?

*

I take the ferry to Alcatraz Island with my sister, who is visiting from Los Angeles, to walk through the new Ai Weiwei exhibit. During the ride, a short 10-minute video promotes the island’s history. The ferry is packed with German and French tourists. The couple sitting next to us is from Florida. Their talk is light and jaunty. He holds a fancy DSLR camera.

We single-file to get out of the ferry once it docks. Once off, visitors are asked to listen to a mandatory 10-minute spiel about the island. When the park ranger asks who in the ferry is here to see the Ai Weiwei exhibit, surprisingly, only a few of us raise our hands, while the rest (about 100) are here to visit the former penitentiary that has now been renovated to a museum, a designated “national recreation area” and a “National Historic Landmark.”

The exhibit itself is spectacular — full of color, hope, and also haunting songs and stories — but admittedly, it feels strange roaming through the former prison cells, its hospital, and dining room. The starkness feels weighted. The buildings have been purposely kept in disrepair (peeling paint, broken windows, burnt-out structures). It’s a place of sadness and violence, but now people pay money to ride the ferry, to take photographs of its haunting hallways.

The museum shop sells coffee cups with photographs of prisoners. Their gaze — forlorn, unhappy, sometimes angry — has forever been made static. Underneath every reproduction, it says, “It’s not criminal to be here! Welcome to Alcatraz!”

R.A. Villanueva, Pt. 2 #writetoday

1.

Consider David Hockney:

“Limitations are really good for you. They are a stimulant. If you were told to make a drawing of a tulip using five lines, or one using a hundred, you’d be more inventive with the five.”

And consider Walker Evans:

"Stare. It is the way to educate your eye and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long."

2.

Now go make something of

FORM

at least 14 lines

a word or phrase that belongs to you

a word or phrase or image that belongs to someone else

ACTION

love

dispute

escape

CONTENT

any animal (living or dead) except birds

anatomy

a haunting